Every year, organisations commit valuable time, money and other resources on trying to improve the competencies of the current and emerging leaders. In a recent survey of over 500 executives, all listed leadership development as one of their top three current and future priorities and two-thirds said it was their top priority. Yet in a different survey by a leading UK Business School, only 7% of senior managers thought that their companies were successful in developing future leaders.

So what is going wrong? Here are four aspects we have identified.

Context

Context is a critical component of successful leadership. A brilliant leader in one situation does not necessarily perform well in another. Too many development initiatives are founded on the assumption that one size fits all and that the same group of skills or style of leadership is appropriate regardless of strategy, organisational culture, or CEO mandate.

Companies planning a leadership initiative should ask themselves a simple question: what, precisely, is this programme for? Focusing on context inevitably means equipping leaders the two or three competencies that will make a significant difference to performance. Instead, they often incorporate a long list of leadership standards, a complex web of dozens of competencies, and corporate-values statements. Each is usually summarised in a seemingly easy-to-remember way (such as the three Rs), and each on its own terms makes sense. In practice, however, what managers and employees often see is an “alphabet soup” of recommendations. When a company cuts through the noise to identify a small number of leadership capabilities essential for success in its business-such as high-quality decision making or stronger coaching skills-it achieves far better outcomes.

Uncoupling reflection from real work

When it comes to planning the programme’s curriculum, companies face a delicate balancing act. On the one hand, there is value in off-site programs (many in university-like settings) that offer participants time to step back and escape the pressing demands of a day job. On the other hand, even after very basic training sessions, adults typically retain just 10 percent of what they hear in classroom lectures, versus nearly two-thirds when they learn by doing. Furthermore, burgeoning leaders, no matter how talented, often struggle to transfer even their most powerful off-site experiences into changed behaviour on the front line.

The answer sounds straightforward – tie leadership development to real on-the-job projects that have a business impact and improve learning. But it’s not easy to create opportunities that simultaneously address high-priority needs and provide personal development. Companies should strive to make every major business project a leadership-development opportunity and to integrate leadership-development components into the projects themselves.

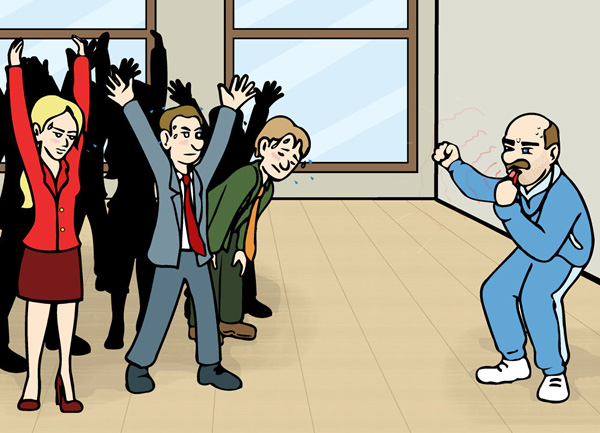

Underestimating mind-sets

Becoming a more effective leader often requires changing behaviour. But although most companies recognize that this also means adjusting underlying mind-sets, too often these organisations are reluctant to address the root causes of why leaders act the way they do. Doing so can be uncomfortable for participants, programme trainers, mentors, and bosses-but if there isn’t a significant degree of discomfort, the chances are that the behaviour won’t change. Just as a coach would view an athlete’s muscle pain as a proper response to training, leaders who are stretching themselves should also feel some discomfort as they struggle to reach new levels of leadership performance.

Identifying some of the deepest, “below the surface” thoughts, feelings, assumptions, and beliefs is usually a precondition of behavioural change-one too often shirked in development programs. Promoting the virtues of delegation and empowerment, for example, is fine in theory, but successful adoption is unlikely if the programme participants have a clear “controlling” mind-set (I can’t lose my grip on the business; I’m personally accountable and only I should make the decisions). It’s true that some personality traits (such as extroversion or introversion) are difficult to shift, but people can change the way they see the world and their values.

Failure to measure results

Companies frequently pay lip service to the importance of developing leadership skills but have no evidence to quantify the value of their investment. When businesses fail to track and measure changes in leadership performance over time, they increase the odds that improvement initiatives won’t be taken seriously.

Too often, any evaluation of leadership development begins and ends with participant feedback; the danger here is that trainers learn to game the system and deliver a syllabus that is more pleasing than challenging to participants. Yet targets can be set and their achievement monitored. Just as in any business-performance programme, once that assessment is complete, leaders can learn from successes and failures over time and make the necessary adjustments.

One approach is to assess the extent of behavioural change, perhaps through a 360 degree-feedback exercise at the beginning of a program and followed by another one after 6 to 12 months. Another is to monitor participants’ career development after the training. How many are subsequently promoted? Finally, try to monitor the business impact by building in appropriate metrics.